Finding Mindfulness in the Ephemeral: A Walk through a New England Woodland

Finding Mindfulness in the Ephemeral:

A Walk through a New England Woodland

Words by Kate Cholakis

Illustrations by Ashley Herrin

Woods with trails. Open fields. Leaves and bugs. When one thinks of a “conservation area,” these images might come to mind. Compared with the vibrant cities, towns, and dramatic state and national parks distributed across New England, smaller conservation areas might not be at the top of everyone’s “must visit” list. To some, they might look the same, with forest stands, occasional openings, mulched trails, and interpretive signs. However, a mindful walk in the woods reveals the special uniqueness of each landscape.

Owned by towns or cities, land trusts, non-profit organizations, or other groups, conservation areas vary widely in the types of plant communities covering the surface (meadows, boreal forest, peat bogs, heathlands), the form of the topography (steep, flat, valley, ridge), the views they provide, and the activities permitted (swimming, picnicking, bicycling, fishing). All of these characteristics combine to shape an experience – a sense of place – that keeps people coming back.

The Trustees of Reservations, a non-profit land trust organization, stewards over 100 properties across Massachusetts. Some sites contain preserved historic homes, like the gilded-age estate at Naumkeag in Stockbridge. Others contain no structures at all but comprise winding trails, rare habitats, and expansive vistas, such as World’s End in Hingham. There really is something for everyone, and the only way to discover a place that speaks to you is to visit these landscapes first-hand.

My favorite way to experience these lands takes a variation on mindfulness. A form of meditation, mindfulness practice encourages people to focus on the present and refrain from judgement or thorough processing of thoughts entering consciousness. What happens when we take mindfulness for a walk in the woods? What will we notice? How will we feel? You might be familiar with studies suggesting the benefits of spending time in a place rich with plants and wildlife. Shinrin-yoku, or “forest bathing,” emerged as a component of preventative health care in Japan. Studies around the globe highlight correlations between spending time outside and strengthened immune systems, lowered blood pressure, decreased stress, improved ability to focus, and reduced inflammation, among others.

One conservation area that comes to mind when I think of “forest bathing” is the Trustees’ Chapel Brook Reservation in Ashfield, Massachusetts. Tucked in along a back road, the site is marked with a sign and informal parking area. To the east of the road, Chapel Brook tumbles spectacularly down a series of ledges, forming the popular destination, Chapel Falls. Today, we turn to the west of the road, wandering up the half-mile Summit Trail to the top of Pony Mountain.

When we arrive at the beginning of the Summit Trail (a bulletin board marks the spot), we notice a giant, smooth rock face soaring upwards through the forest canopy. Sitting on one of the ledges at its base, we gather ourselves, close our eyes, and listen to the sounds of rustling leaves, singing birds, and the stream making its way towards the dramatic falls on the other side of the road. We listen to our breath and feel the dappled sunlight on our faces. When a thought emerges, we imagine it floating away (perhaps down the stream). We arrive.

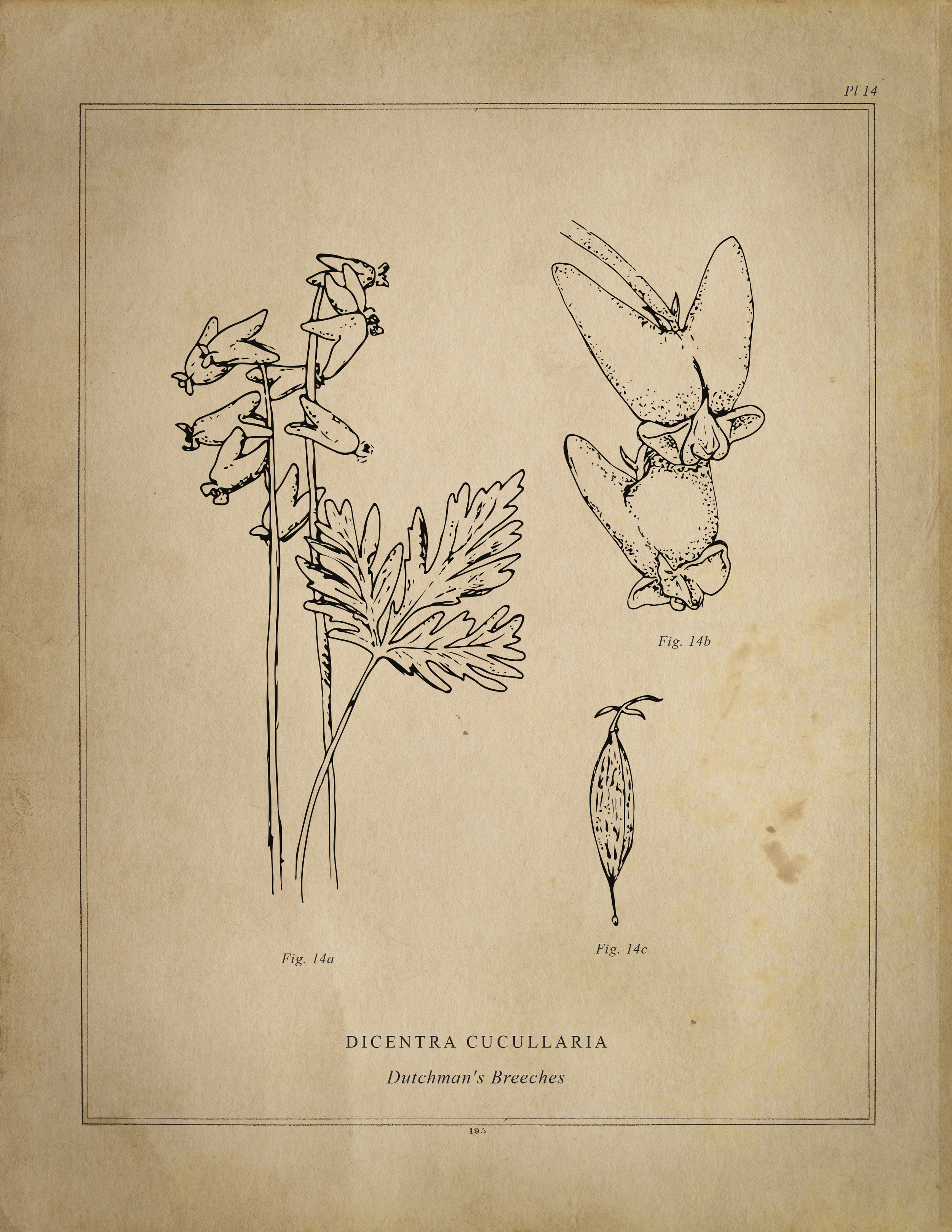

We bat open our eyes, hop off the rock, and continue on the trail, which wraps around boulders hugging the side of Pony Mountain. A creek, a Chapel Brook tributary, runs parallel to the trail to the left. Beyond the creek, another hillside slopes upwards to the west, cradling us within a small, southeast-facing valley, a concave pocket. Moving slowly along the trail, we notice hundreds of spotted green leaves poking up through the composting leaf litter, elongated like fish. Several have short stalks with a tiny yellow, bell-shaped lily. You need to crouch down to see the familiar, star-like petals. If the trout lily (Erythronium americanum) is not delicate enough, another small plant bears flowers shaped like the tiniest pair of white pantaloons. You cannot help but smile when holding Dutchman’s Breeches (Dicentra cucullaria) in your fingertips, admiring how the pants are suspended from a stem as if hanging from a clothesline. The pant-like flowers emerge just as their pollinator – the native bumblebee – wakes up for the season.

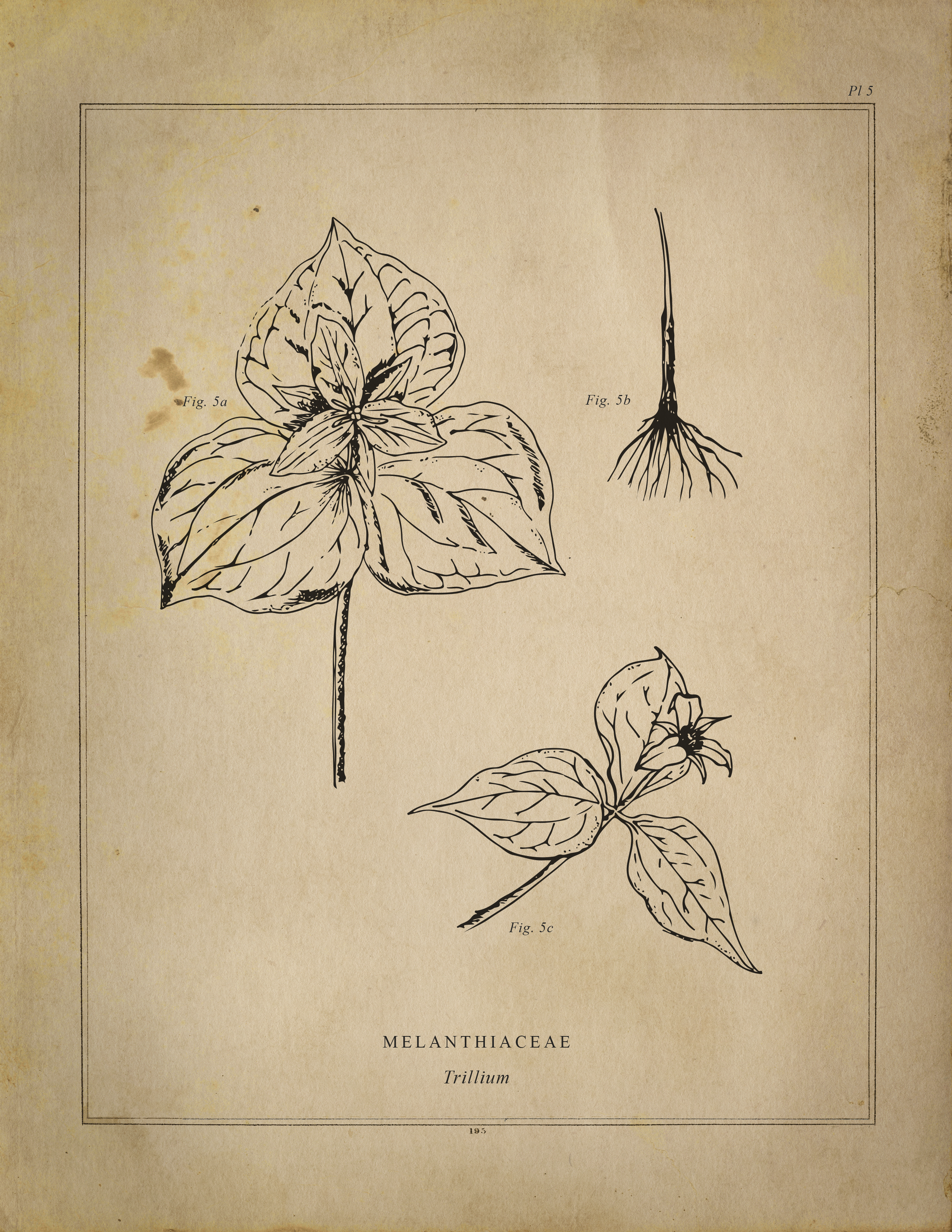

Lifting your head and looking across the ground level of the forest, you notice slightly taller wildflower stalks with three leaves (which are actually bracts, or modified leaves) and flowers with three maroon petals and three green sepals. This flower, Trillium, seems so simply geometric, almost confident.

Referred to as spring ephemerals, these wildflowers grow, bloom, and shrivel down into dormancy during a very short window in early spring. They need to produce seeds for the next generation between snowmelt and the leafing out of canopy trees above. The insects that pollinate them wake up around this same time of the year. Many ephemerals rely on ants for seed dispersal. As a result, these populations do not spread particularly far, being limited by the range of the ant.

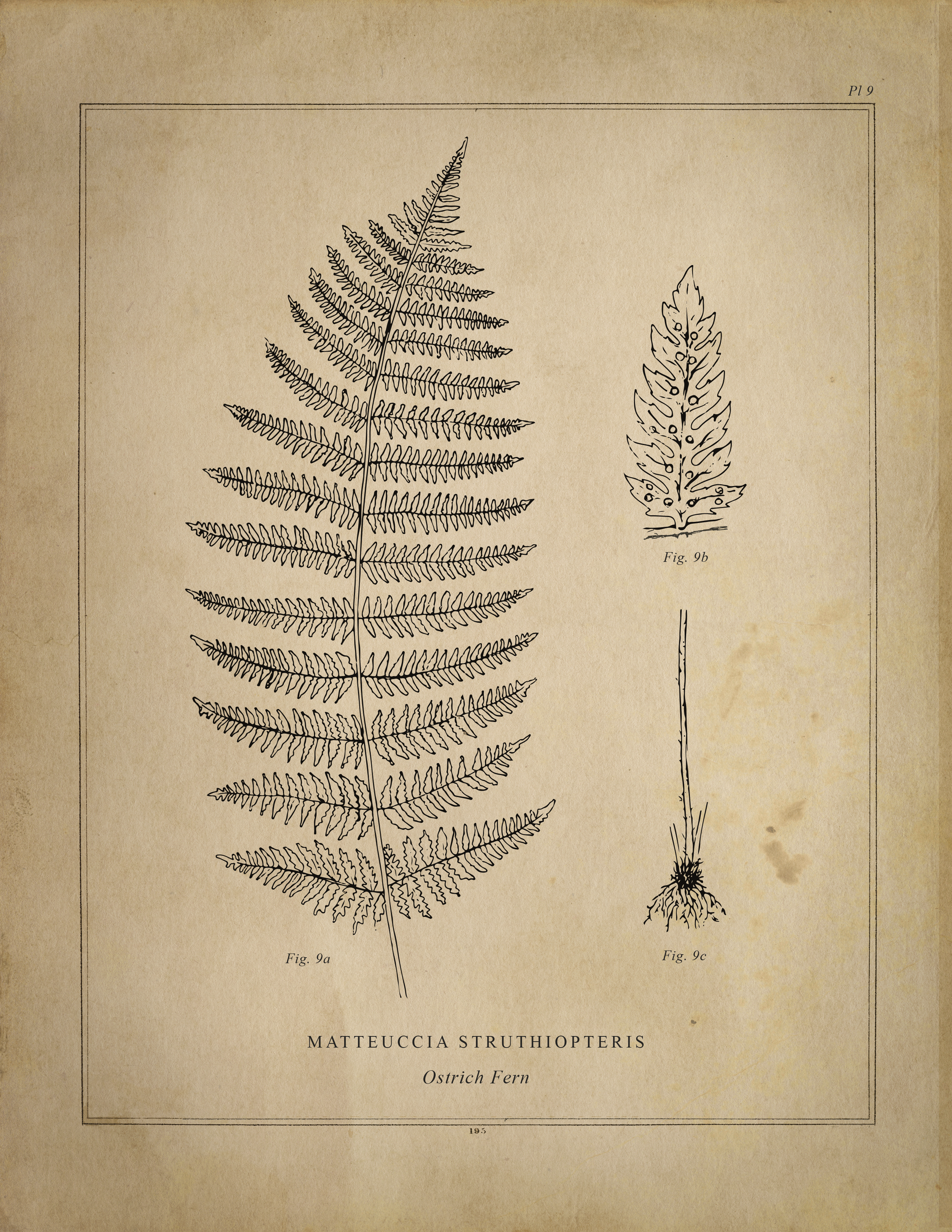

Looking across the river and up the opposite hillside, you notice that these plants cover the land in a shifting mosaic with patches of color and texture. The lush green rises out from the brown leaf litter with a strong force, particularly in comparison with the open canopy above, where the leaves of the trees have barely emerged from their buds. We realize, all of a sudden, that we are in a particularly lush, green place with a diversity of flowers and ferns. We might not realize that all of the factors that we notice (the slope, the aspect, the stream, the vegetation), combine to form a special kind of habitat: rich mesic forests grow in deep, nutrient-rich soils at lower elevations. Understory spring ephemeral wildflowers thrive in the rich organic matter, soaking up the sun from their south-facing aspect just before the larger trees shade them out.

The timing seems perfect, almost unbelievably so. Yet, many of these wildflower populations are susceptible to decline due to destroyed and fragmented habitat, collection by people, and other factors. We leave these delicate plants as they are along the trail, continuing up the mountain to the summit, where a sweeping view extends across the surrounding landscape.

Our eyes adjust from the scale at which we observed the tiniest of wildflowers to the infinitely long view of the horizon. In a few weeks, a blanket of green leaves will conceal the valley below. This canopy will extend into the distance, beyond the conservation area’s property lines. It will conceal many other unique habitats and hidden treasures. The only way to find them is to pull over by the side of the road, and walk up the trail.